A new analysis of corruption and corruption reform in the electricity sectors of Ghana and Kenya suggests a new interpretation of how and why successes against corruption seem so elusive. This analysis makes sense of the apparent paradox that development projects can have positive outcomes whilst being beset with large-scale and ongoing corruption. To what extent is the reporting of the corruption overdone and with what consequence? To what extent are successful reforms unrecognised?

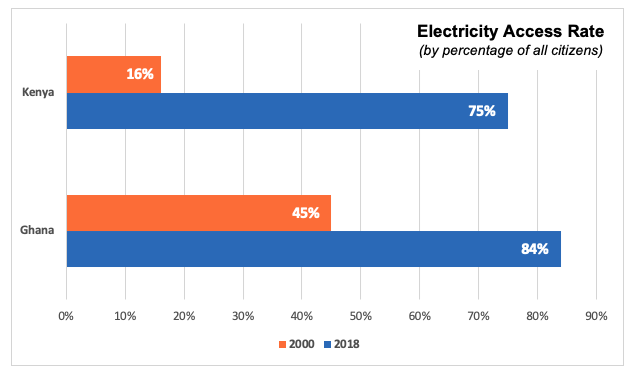

In both Ghana and Kenya, the electricity access rate has risen spectacularly, yet the electricity distributors in both countries have been – and still are – perceived by the public as systemically corrupt.

The public perception of unbridled corruption in the Kenyan energy sector reached a point so extreme in the 1990s that it prompted a donor embargo of the energy sector. New policies had to be urgently implemented to attract private sector participation to complement the state’s efforts. In response, Kenya changed from an incremental planning approach to ‘transformational’ energy planning in urban areas, via amending the Electricity Act and National Energy Policy to allow for private sector players and for open access to the National Grid.

While there were numerous corruption scandals during this transformation, it was this change that led to the elimination of power deficits and a much-improved electricity access for citizens. In rural areas, where access had been minimal, the new initiatives focused predominantly on subsidized rural electrification initiatives.

Meanwhile in Ghana, parastatals involved in power generation and supply have done creditably well to improve both electricity distribution and citizens’ access to electrical grids. Nonetheless, there have been multiple accusations and cases of corruption. The introduction of more pre-paid meters, for instance, coincided with tariff increases, which led to the perception that the new meters were either (a) deliberately calibrated to subtly extort exorbitant tariffs from customers, or (b) faulty and recording electricity consumption much faster than units consumed. This also happened to coincide with Usain Bolt’s sterling performance in the 2016 Olympics, which made him a household name in Ghana and, hence the invention of the satirical term ‘Usain-Bolt’ pre-paid meters by disgruntled customers.

On the positive side, there were numerous improvements in the way electricity programmes were rolled out, leading both to better access and reduced abuse through corruption. The cancellation of grid expansion contracts, legal prosecution of allegedly corrupt officials in Kenya, fierce public criticism of Ghanaian governments in the most controversial deal, etc. have also registered significant successes. Other successful corruption reforms included many ‘problem-solving’ measures, such as the frequent monitoring of electricity infrastructure, introduction of pre-paid metering systems, improved revenue collection/tariff payment mechanisms, establishment of legal frameworks to punish criminals involved in power thefts, improved oversight roles of civil society organizations, and stricter media scrutiny in the procurement of electricity infrastructure.

Performance reforms and specific anti-corruption measures in the electricity sectors of both Kenya and Ghana have generated an intricate co-mingling of partially successful reforms bundled with partial failures. Major improvements in the delivery of specific services have been obscured, however, by the failures of other anti-corruption initiatives seeking to address more deeply embedded, institutional corruption.

Anti-corruption progress in such complex and politically charged infrastructure developments is likely to comprise a co-mingling of successful and failed reforms. However, the nature of the media reporting and public discourse surrounding corruption, which focus exclusively on negative experiences and failed reforms, and the ongoing, seemingly insoluble, elite corruption mean that successful measures will not be explicitly recognised or given any attention.